Page to Screen: In Cold Blood

In Cold Blood has become so much more than non fiction since its birth, it has birthed non fiction true crime. Here I look into what it did for our understanding of human wickedness, how it was portrayed on screen (in 1967, not the 1996 version) and the Philip Seymour Hoffman biopic of its author Truman Capote.

The problem of horrible human behaviour which nonetheless fascinates us, is because we are human and therefore capable of the best and worst of it; this is why true crime sells. Acts by humans which seem so beyond the normal, which seem so wicked and cruel, possess us because they do not seem too far away from us. They are within touching distance. Few, however, have had such an intimate relationship with killers and their killings as Truman Capote.

In Cold Blood’s narrative journey from page to its cinema adaptation was brought back to base with the biopic, Capote. Together they make for a fascinating study of the motives, means and methods of storytelling and our relationship with criminality- and mortality.

THE BOOK

“Somehow he haunts me the most, Kenyon does. I think it’s because he was the most recognisable, the one that looked the most like himself - even though he’d been shot in the face.”

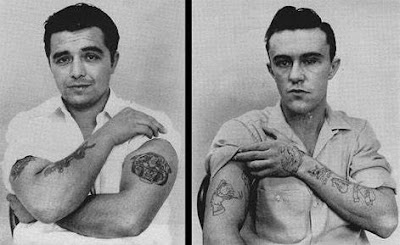

Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood was revolutionary and it still is the gold standard for true crime; exemplary research skillfully told. It is probably my hardest Page to Screen to write, too, such is its depth and craft. Published as a book in 1966, Capote’s obsessively investigated and poetically prosaic portrayal on the 1959 annihilation of the Clutter family in Kansas by two previously petty criminal nomads, Richard Hickock and Perry Smith, is structured with complex simplicity.

Investigating before the killers were even caught, Capote got so deep into the horror he came out the other side of the crime and befriended one of the killers. In Cold Blood is a journey from the innocence of the Clutters to the horror and outrage of their killing, to an understanding of the perpetrators. This ability to emote with all of the subjects of his book was what made Capote’s text so shocking and unique, humans still don’t like admitting how easy it is for us to kill.

Told like fiction, visually written with rich detail gleaned from research and interviews, In Cold Blood still fills in a lot of blanks. It has received criticism for Truman’s use of artistic licence where fact was in doubt or unavailable. Despite this, that technique has become common in a lot of contemporary true crime media- notably in the hugely popular podcasting world which thrives on creative conjecture to create an easily consumable product containing no gaps. Subjectivity and speculation are now the norm.

This understanding is what was controversial, but it marries with his cynicism of American wholesomeness. The Clutters are the embodiment of the nuclear family, salt of the earth, hard working, God fearing Americans. Capote inches ever closer to these soon to be victims he brings to life so well’s demise with salt in his mouth. The Bible Belt, in Capote’s words is a, “Gospel haunted strip of American territory in which a man must, if only for business reasons, take his religion with the straightest of faces.”.

The slow spread of information is both sad and salacious, and a perfect contrast with our now incessant obsession with current catastrophes. “The suffering. The horror. They were dead. A whole family. Gentle, kind people, people you knew - murdered. You had to believe it, because it was really true.”

Rumour and theory and fact are all gossip, and horror, the horror, indeed. Capote builds the scene well, as the Clutter family’s routine existence is circled and then destroyed by two untethered perverts. In Cold Blood is compulsory, compelling reading created in a time which wasn’t wholly ready to receive it.

“Did you see those guys? They coulda robbed us!”

“What of?”

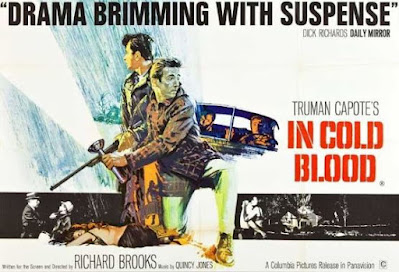

Released in 1967, In Cold Blood’s monochrome, cinematic sibling must surely have been in production since its written parent, which was published piecemeal from 1965. Capote allegedly profited hugely from this, and why not. Snapping the story up is understandable and admirable forethought by the producers who by the standards of the day do their best to create celluloid with as much weight as Truman Capote’s words. Sadly, it doesn’t hold up on screen. Richard Brooks’ telling, with Robert Blake and Scott Wilson as Dick and Perry, falls foul of just simply being too old to be powerful anymore.

Almost a road trip, a lads on the lam caper which makes being a drifter seem fun; these two crims encounter good fried food and cooked to order eggs, all while making smoking look cool. Richard Hickock and Perry Smith are ubiquitous criminals of their day portrayed with little depth by actors capable of better. Banal and boring, which is at least somewhat appropriate given the text, they sweep their hair and utter tacky threats mostly without any complexity or malice of character.

Yes In Cold Blood is well filmed, even innovative for its day but the leads look at least ten years too old, at least, and a dated score again ages it, and not in a charming way. Much like many other films of its era, not being in its era detracts from any pioneering originality it once held. Its power has been dulled by time, unlike the book.

There’s too much comment and morality of its time unsubtly woven into In Cold Blood. Capote deferred most of the judgement to the reader, as a viewer the film does not allow you the same moral leeway. Atheism is an early nod to criminality, because godless and faithful are the perfect black/white divide if you’re clumsy and biased. That’s not to say the Clutters’ deaths weren’t the horrible juxtaposition of respectable believers and scumbags, but it’s too clumsy a line to draw on screen.

In Cold Blood internalises the thoughts and motivations of the killers a lot, and makes Perry more sympathetic than Dick. The killers eventually accept their own killing and Truman Capote is pretty absent from the story during this period, which is in contrast to his book and biopic Capote. It's very well shot and set up and strangely anti-execution for the sixties in America. Even now the execution debate rages.

As a film, compared to the book, In Cold Blood is unsatisfying. It’s hard to make anything look bad in black and white, least of all murder and chokety-snap justice, but what impact it held has faded like a knockout punch thrown decades ago.

"The obvious answer is that eventually, I mean, I'll kill myself... without meaning to."

Truman Capote

Covering Truman Capote’s deep dive into the Clutter’s awful killings, Capote is a literal and metaphorical journey through the creative process and its effects on an already troubled man. Assisted by friend and famed novelist Harper Lee, Truman goes on an elongated ego tip and meltdown. He is sometimes brilliant but never perfect, hard work but great company, and then there’s the difficulty of his relationship with two killers.

The late, great, Philip Seymour Hoffman won an Oscar for his iconic portrayal of Truman Capote and Bennett Miller’s superb film forms a base of understanding to Truman’s text which ironically probably fills in as many blanks as Capote did himself writing In Cold Blood. How true is it? How true is the film about the true crime book about a true crime crime? How much do you care about truth when what we’re really here for is human understanding?

Capote posits different, difficult questions: from reflection on human nature to its subject’s cause celebre and Truman Capote’s own nature. Much like the book, it lets you decide where you fall.

Perhaps Capote is more accurate about the author than it is about what he was reporting on. Perhaps. Truman Capote spoke thoughtfully and convincingly with his written words, but egotistically and softly with his spoken one, that dichotomy so prevalent in his persona Seymour Hoffman could not have captured more perfectly. What is so sad in retrospect is that Capote's death to drug and alcohol related causes was echoed in his conduit Seymour Hoffman’s demise, with a recurring heroin addiction hitting a deathly tone.

Truman Capote is us, both in the book and this film. We've got the story about the crime which was groundbreaking, and then we've got this story about the man who told the groundbreaking tale of the crime. A man who is then tied intrinsically to the crime for its murderers and yet was hurt deeply by it and its consequences to the murderers. Capote vocally decried the death penalty after watching the double execution.

Capote makes In Cold Blood as a film redundant. Read the book and watch Capote, you don't need to see the film, it's lost its power, it's lost its potency, it's no longer shocking. Worst, In Cold Blood’s cinema-sibling is no longer relevant to the problem of evil. Some things die when they get older, but they haven't In Truman Capote’s writing or biopic. Capote is captivating, challenging cinema which reflects every power and beauty of its page preceding it.

IN CONCLUSION

Someone able to understand and describe criminals, a murder so obscene and the charming, sedate farmland which was shattered by them was something new when In Cold Blood hit the shelves. It still remains something abstract, that isn't the norm and I don't think it ever will be, very few people are capable of what Truman Capote achieved. The Clutters’ awful murder is astonishingly awful and something still unusual in its random nature. The lens of Truman Capote, that ability to understand and embody in writing every single element is exceptional, but his true genius is showing us empathy, even if it came at cost to himself.

Truman knew he was on a pathway to destruction and that also is an enduringly sad reflection on the human condition. We can destroy ourselves. We will destroy ourselves. We will destroy ourselves doing things we know will destroy us. Sometimes we’ll do something worthwhile before that, Truman Capote and Philp Seymour Hoffman did.

Comments

Post a Comment